Design Thinking

One of the problems with analysing data is the potential to get trapped in the past, when we could be imagining the future. Past performance can be no indication of future success, especially when it comes to Google’s shifting whims.

We see problems, we devise a solution. But projecting forward by measuring the past, and coming up with “the best solution” may lead to missing some obvious opportunities.

Design Thinking

In 1972, psychologist, architect and design researcher Bryan Lawson created an empirical study to understand the difference between problem-based solvers and solution-based solvers. He took two groups of students – final year students in architecture and post-graduate science students – and asked them to create one-story structures from a set of colored blocks. The perimeter of the building was to optimize either the red or the blue color, however, there were unspecified rules governing the placement and relationship of some of the blocks.

Lawson found that:The scientists adopted a technique of trying out a series of designs which used as many different blocks and combinations of blocks as possible as quickly as possible. Thus they tried to maximize the information available to them about the allowed combinations. If they could discover the rule governing which combinations of blocks were allowed they could then search for an arrangement which would optimize the required color around the design. By contrast, the architects selected their blocks in order to achieve the appropriately colored perimeter. If this proved not to be an acceptable combination, then the next most favorably colored block combination would be substituted and so on until an acceptable solution was discovered.

Nigel Cross concludes from Lawson's studies that "scientific problem solving is done by analysis, while designers problem solve through synthesis”

Design thinking tends to start with the solution, rather than the problem. A lot of problem based-thinking focuses on finding the one correct solution to a problem, whereas design thinking tends to offer a variety of solutions around a common theme. It’s a different mindset.

One of the criticisms of Google, made by Google’s former design leader Douglas Bowman, was that Google were too data centric in their decision making:

When a company is filled with engineers, it turns to engineering to solve problems. Reduce each decision to a simple logic problem. Remove all subjectivity and just look at the data...that data eventually becomes a crutch for every decision, paralyzing the company and preventing it from making any daring design decisions…

There’s nothing wrong with being data-driven, of course. It’s essential. However, if companies only think in those terms, then they may be missing opportunities. If we imagine “what could be”, rather than looking at “what was”, opportunities present themselves. Google realise this, too, which is why they have Google X, a division devoted to imagining the future.

What search terms might people use that don’t necessarily show up on keyword mining tools? What search terms will people use six months from now in our vertical? Will customers contact us more often if we target them this way, rather than that way? Does our copy connect with our customers, of just search engines? Given Google is withholding more search referral data, which is making it harder to target keywords, adding some design thinking to the mix, if you don’t already, might prove useful.

Tools For Design Thinking

In the book, Designing For Growth, authors Jeanne Liedtka and Tim Ogilvie outline some tools for thinking about opportunities and business in ways that aren’t data-driven. One famous proponent of the intuitive, design-led approach was, of course, Steve Jobs.

It's really hard to design products by focus groups. A lot of times, people don't know what they want until you show it to them

The iphone or iPad couldn’t have been designed by looking solely at the past. They mostly came about because Jobs had an innate understanding of what people wanted. He was proven right by the resulting sales volume.

Design starts with empathy. It forces you to put yourself in the customers shoes. It means identifying real people with real problems.

In order to do this, we need to put past data aside and watch people, listen to people, and talk with people. The simple act of doing this is a rich source of keyword and business ideas because people often frame a problem in ways you may not expect.

For example, a lot of people see stopping smoking as a goal-setting issue, like a fitness regime, rather than a medical issue. Advertising copy based around medical terminology and keywords might not work as well as copy oriented around goal setting and achieving physical fitness. This shift in the frame of reference certainly conjures up an entirely different world of ad copy, and possibly keywords, too. That different frame might be difficult to determine from analytics and keyword trends alone, but might be relatively easy to spot simply by talking to potential customers.

Four Questions

Designing For Growth is worth a read if you’re feeling bogged down in data and looking for new ways to tackle problems and develop new opportunities. I don’t think there’s anything particularly new in it, and it can come across as "the shiny new buzzword" at times, but the fundamental ideas are strong. I think there is value in applying some of these ideas directly to current SEO issues.

Designing For Growth recommends asking the following questions.

What is?

What is the current reality? What is the problem your customers are trying to solve? Xerox solved a problem customers didn’t even know that had when Xerox invented the fax machine. Same goes for the Polaroid camera. And the microwave oven. Customers probably couldn’t describe those things until they saw and understood them, but the problem would have been evident had someone looked closely at the problems they faced i.e. people really wanted faster, easier ways of completing common tasks.

What do your customers most dislike about the current state of affairs? About your industry? How often do you ask them?

One way of representing this information is with a flowchart. Map the current user experience from when they have a problem, to imagining keywords, to searching, to seeing the results, to clicking on one of those results, to finding your site, interacting to your site, to taking desired action. Could any of the results or steps be better?

Usability tests use the same method. It’s good to watch actual customers as they do this, if possible. Conduct a few interviews. Ask questions. Listen to the language people use. We can glean some of this information from data mining, but there’s a lot more we can get by direct observation, especially when people don’t click on something, as non-activity seldom registers in a meaningful way in analytics.

What if?

What would “something better” look like?

Rather than think in terms of what is practical and the constraints that might prevent you from doing something, imagine what an ideal solution would look like if it weren’t for those practicalities and constraints.

Perhaps draw pictures. Make mock-ups. Tell a story. Anything that fires the imagination. Use emotion. Intuition. Feeling. Just going through such a process will lead to making connections that are difficult to make by staring at a spreadsheet.

A lot of usability testers create personas. These are fictional characters based on real or potential customers and are used try to gain an understanding of what they might search for, what problems they are trying to solve, and what they expect to see on our site. Is this persona a busy person? Well educated? Do they use the internet a lot? Are they buying for themselves, or on behalf of others? Do they tend to react emotionally, or are they logical? What incentives would this persona respond to?

Personas tend to work best when they’re based on actual people. Watch and observe. Read up on relevant case studies. Trawl back through your emails from customers. Make use of story-boards to capture their potential actions and thoughts. Stories are great ways to understand motivations and thoughts.

What are those things your competition does, and how could they be better? What would those things look like in the best possible world, a world free of constraints?

What wows?

“What wows” is especially important for social media and SEO going forward.

Consider Matt Cutts statement about frogs:

Those other sites are not bringing additional value. While they’re not duplicates they bring nothing new to the table. It’s not that there’s anything wrong with what these people have done, but they should not expect this type of content to rank.

Google would seek to detect that there is no real differentiation between these results and show only one of them so we could offer users different types of sites in the other search results

Cutts talks about the creation of new value. If one site is saying pretty much the same as another site, then those sites may not be duplicates, but one is not adding much in the way of value, either. The new site may be relegated simply for being “too samey”.

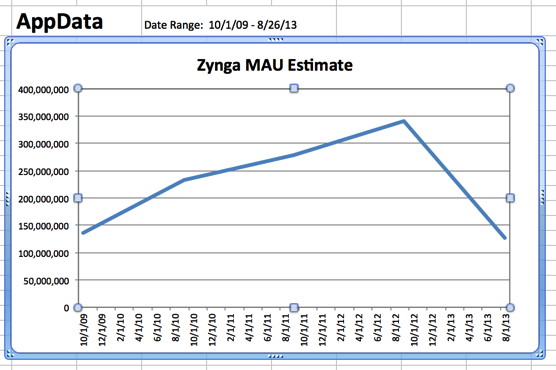

It's the opposite of the Zygna path:

"I don't fucking want innovation," an anonymous ex-employee recalls Pincus saying in 2010, according to the SF Weekly. "You're not smarter than your competitor. Just copy what they do and do it until you get their numbers."

Generally speaking, up-and-coming sites should focus on wowing their audience with added depth and/or a new perspective. This, in turn, means having something worth remarking upon, which then attracts mentions across social media, and generates more links.

Is this certain to happen? Nothing is certain as far as Google is concerned. They could still bury you on a whim, but wowing an audience is a better bet than simply imitating long-established players using similar content and link structures. At some point, those long-established players had to wow their audience to get the attention and rankings they enjoy today. They did something remarkably different at some point. Instead of digging the same hole deeper, dig a new hole.

In SEO, change tends to be experimental. It’s iterative. We’re not quite sure what works ahead of time, and no amount of measuring the past tells us all we want to know, but we try a few things and see what works. If a site is not ranking well, we try something else, until it does.

Which leads us to….

What works?

Do searchers go for it? Do they do that thing we want them to do, which is click on an ad, or sign up, or buy something?

SEOs are pretty accomplished at this step. Experimentation in areas that are difficult to quantify - the algorithms - have been an intrinsic part of SEO.

The tricky part is not all things work the same everywhere & much like modern health pathologies, Google has clever delays in their algorithms:

Many modern public health pathologies – obesity, substance abuse, smoking – share a common trait: the people affected by them are failing to manage something whose cause and effect are separated by a huge amount of time and space. If every drag on a cigarette brought up a tumour, it would be much harder to start smoking and much easier to quit.

One site's rankings are more stable because another person can't get around the sandbox or their links get them penalized. The same strategy and those same links might work great for another site.

Changes in user behavior are more directly & immediately measurable than SEO.

Consider using change experiments as an opportunity to open up a conversation with potential users. “Do you like our changes? Tell us”. Perhaps use a prompt asking people to initiate a chat, or participate on a poll. Engagement that has many benefits. It will likely prevent a fast click back, you get to see the words people use and how they frame their problems, and you learn more about them. You become more responsive and empathetic sympathetic to their needs.

Beyond Design Thinking

There’s more detail to design thinking, but, really, it’s mostly just common sense. Another framework to add, especially if you feel you’re getting stuck in faceless data.

Design thinking is not a panacea. It is a process, just as Six Sigma is a process. Both have their place in the modern enterprise. The quest for efficiency hasn't gone away and in fact, in our economically straitened times, it's sensible to search for ever more rigorous savings anywhere you can

What's best about it, I feel, is this type of thinking helps break strategy and data problems down and give it a human face.

In this world, designers can continue to create extraordinary value. They are the people who have, or could have, the laterality needed to solve problems, the sensing skills needed to hear what the world wants, and the databases required to build for the long haul and the big trajectories. Designers can be definers, making the world more intelligible, more habitable

New to the site? Join for Free and get over $300 of free SEO software.

Once you set up your free account you can comment on our blog, and you are eligible to receive our search engine success SEO newsletter.

Already have an account? Login to share your opinions.

Comments

Add new comment